When we talk about openness to change, there is one aspect that tends to fall by the wayside, which is that, like all skills, it too can be trained. For companies, effective change training is now fundamental and necessary, but how can it be done? There are three issues worth emphasizing: timing, modality, and, most importantly, the emotionality of the people involved.

Green shifts, technological innovations, generational contrasts, new employee needs: the world of work is in an evolutionary maelstrom that shows no signs of slowing down, and this, while interesting in theory, in practice poses different every day challenges for Managers and companies, who must find ways to adapt themselves and teams to an environment whose hallmark is change.

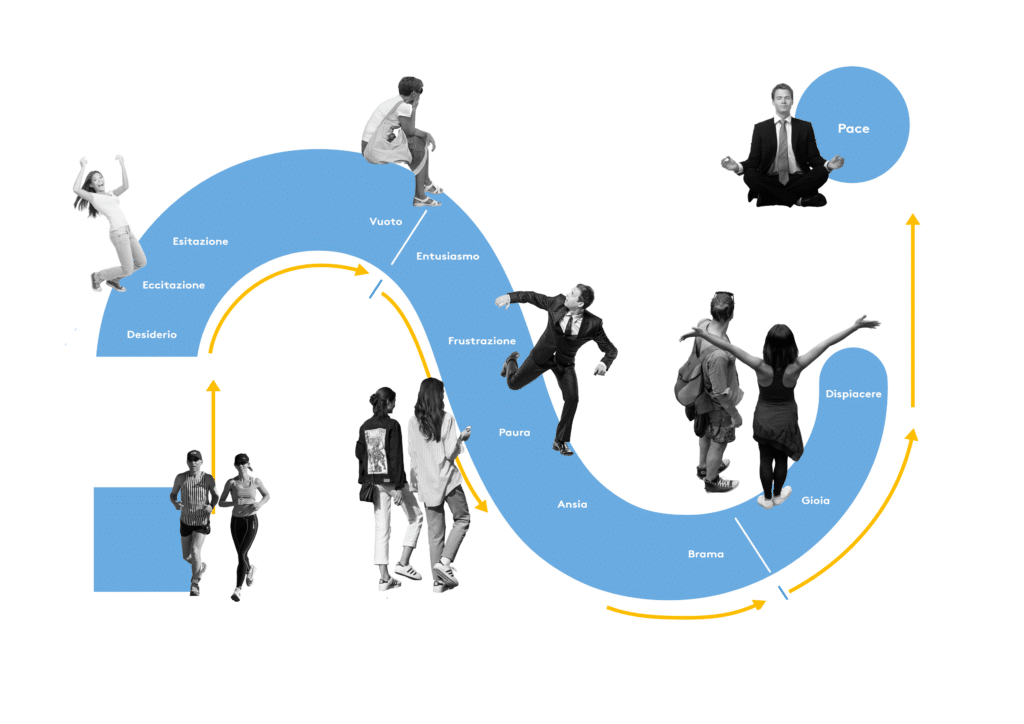

Change, we know, is complex: change is not a linear path, from point A to point B, but, as the Swiss psychiatrist Kübler-Ross theorized, it follows a curve that goes through seven stages (Shock, Rejection, Frustration, Depression, Experimentation, Decision, Integration), only at the end of which change can be considered as assimilated. In the workplace, breaking habits and creating new ones can result in misalignments, frustration, or lower engagement, with negative relational and performance results for companies.

The good news, however, is that the attitude to change, like all skills, can be trained. Having Managers who know how to convey a good attitude to change can bring virtuous behaviors to the company in managing what evolves.

The emotions of change

When changing, one must start with the human factor: in fact, the organization is composed of people, and how these people experience newness is central to determining whether or not a process is successful.

Hostility to change, in general, can find its origin in four types of behaviors or emotions:

- conservative mindset, which represents change as the disruption of a functioning status quo

- laziness, which causes adaptation to be interpreted as an enormous effort

- fear, as novelty appears complex and makes one fear that he or she will not cope

- contentment, typical of when one is comfortable in the current situation and sees no reason to change it.

Just as the emotional side of people can create an obstacle to implementing changes, however, the opposite is also true, namely that positive emotions can be a great lever to embrace them and carry them through effectively.

The close correlation between new habits and emotions is underscored by BJ Fogg, founder of Stanford’s Behavioural Design Lab:, in his book The Tiny Habits Method, the small-step Revolution, he devotes an entire chapter to this topic, pointing out that “there is a direct correlation between the feeling generated by a behavior and the likelihood of repeating it in the future.” “Habits,” he continues, “can form very quickly, often within a few days, as long as the behavior is associated with a positive emotion. […] Emotions create habits. The secret is not frequency, repetition, or the magic formula. It is the emotion. So in planning the adoption of new habits you are planning emotions.”

At the corporate level, then, it is important for Managers to always have the emotional pulse of how employees are experiencing the proposed changes, and this means that they will need to bring to bear certain skills that become necessary at a time of transition: clear interpersonal communication, to explain why a change is being made and resolve any doubts; soliciting feedback and giving support when the emotional curve of change goes down; and motivating and teaming up when the curve starts to rise again.

Regarding this last point (motivating), it is again Fogg who explains how much the celebration of a small new action can influence the rooting of a big new habit: recognizing in employees, even through a compliment or a smile, the effort made and the result achieved for each small step taken, generates in them what is called “shine,” a positive emotion, a mixture of pride, recognition and involvement “that induces the brain to encode the new behavior as an automatism.”

Clarity, positive emotions, and celebrations, then, are essential components in breaking down the natural emotional barriers people have to the new and training a culture conducive to change.

But in practice, how do you introduce new habits in the company?

To kick-start a habit, it is important to take into consideration three aspects: the most obvious, which is likely to be the only one we focus on, is the what, the change you want to implement. Equally important, however, should be the when and the how, especially in contexts, such as the corporate one, in which the emotional carry of multiple people coexists.

In his book When, the Science Secrets of Choosing the Right Time, Daniel H. Pink even talks about “taking the when seriously,” emphasizing the importance of beginnings (at the right time). Some periods or days can be called fresh starts, that is, moments with which, for social or personal issues, one associates the idea of starting from scratch: in daily life, it may be Monday, in the business context, on the other hand, it could be September or a new quarter or an important anniversary for the organization. Taking a day and turning it into a new beginning means loading it with a symbolic value that becomes even greater if it is shared by the whole team: that date will be experienced by more people with a sense of expectation, hope, and desire and will generate those positive emotions that beginnings know how to stimulate. And positive emotions in change we have already seen how relevant they can be.

Let us now come to the how.

Changing habits means generating new behaviors. Fogg, again in The Tiny Habits Method, points out that “behaviors are like bicycles, they may have different shapes and colors, but the basic mechanisms are always the same: wheels, brakes, pedals.” Based on this assumption, he elaborates the theory, applicable in 100 percent of cases, that Behaviors are made from Motivation (the desire to act), Ability (the ability to perform it) and Trigger (the stimulus that prompts action).

There is often a tendency to think that Motivation is the main lever in a change, but Fogg explains that this is not the case: while its importance is unquestionable, it is also undeniable that it is the most fickle and least constant aspect (we are talking, let’s remember, about people, by their essence subject to emotional changes). That is why it cannot be completely relied upon: certainly, the stronger the motivation the more likely the action is to occur, but in the long run the motivation may wane or no longer suffice.

In our work as coaches, the Trigger assumes great importance. In corporate contexts, the impetus for change can also come from value, organizational, and cultural issues: but how to do this if there are people who do not feel that corporate values are entirely their own? How to be able to have an effective graft on them as well? This is where interpersonal communication comes in handy again: the more you communicate, the more you take into account different points of view, and the more you will proceed in training people in the usefulness of adapting to change.

Finally, we come to Ability: assuming that everyone involved can enact change, a method must be applied to prevent fear and feelings of not being up to par from taking over. James Clear, in his text Atomic Habits, Small Habits for Big Change, points out that habits are made in building blocks, small bricks to be placed one on top of the other, each essential for the big result: “a slight change in daily habits can lead our lives to very different destinations. […] Success is the product of daily habits, not transformations that are made once in a lifetime.” To describe how to bring about new habits, he elaborates on four steps that can also be applied to business contexts before proceeding with a change process.

Let’s take an example: a company wants to become B-Corp certified.

- Make it obvious: become aware of business habits that go for or against greater sustainability in the organization, make a list of them, and write down which ones should be kept, strengthened, or eliminated

- Make it appealing: present the certification journey to employees by highlighting the positives, including differentiated speeches based on the person in front of you

- Make it easy: This is the focus here. Start with short-term goals, actions that can easily be incorporated without effort and without upsetting everyone’s pre-existing habits

- Make it satisfying: make all employees participate by showing results, complimenting each person’s efforts, and granting recognition (even verbal) for each small step.

Thus, by putting the focus on the emotional aspect, the timing, and how changes are proposed and promoted within a company, a change-friendly attitude can be trained.

The result will be an organization that has people within it with less fear and more confidence and openness to the new and therefore more ready to face the changes, even major ones, that tomorrow may present.